VITAMIN C

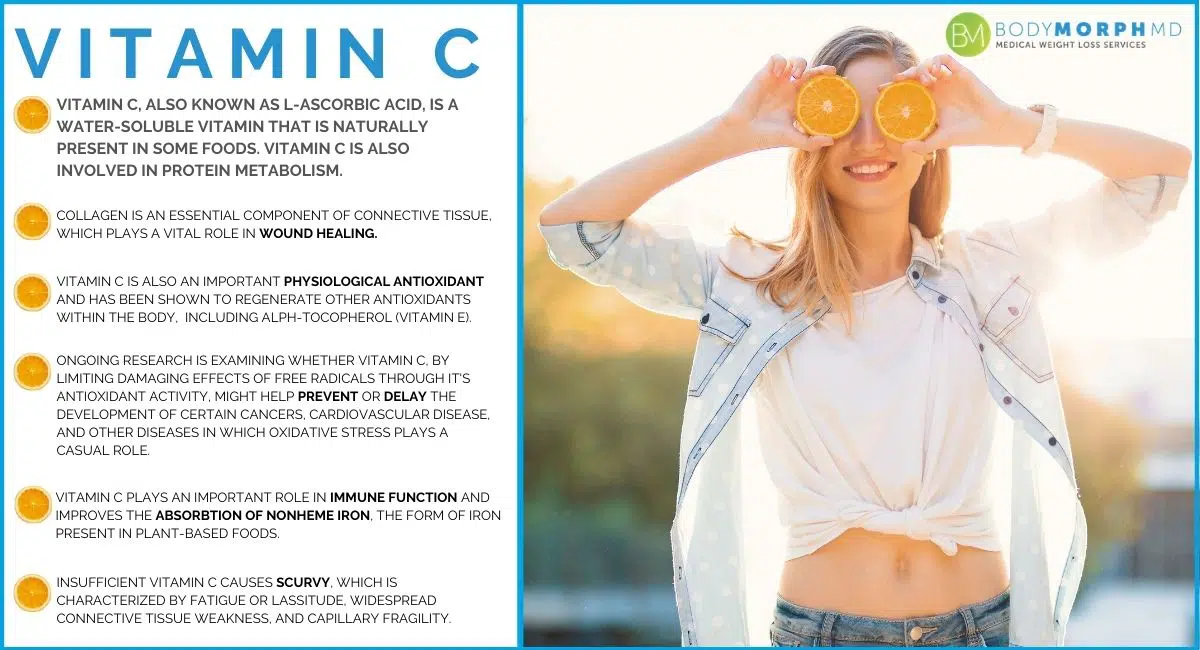

Vitamin C, also known as L-ascorbic acid, is a water-soluble vitamin that is naturally present in some foods.Vitamin C is also involved in protein metabolism [1,2].

- Collagen is an essential component of connective tissue, which plays a vital role in wound healing.

- Vitamin C is also an important physiological antioxidant [3] and has been shown to regenerate other antioxidants within the body, including alpha-tocopherol (vitamin E) [4].

- Ongoing research is examining whether vitamin C, by limiting the damaging effects of free radicals through its antioxidant activity, might help prevent or delay the development of certain cancers, cardiovascular disease, and other diseases in which oxidative stress plays a causal role.

- Vitamin C plays an important role in immune function [4] and improves the absorption of nonheme iron [5], the form of iron present in plantbased foods.

- Insufficient vitamin C intake causes scurvy, which is characterized by fatigue or lassitude, widespread connective tissue weakness, and capillary fragility [1,2,4,6-9].

WOUND HEALING

The major function of vitamin C (ascorbic acid) in wound healing is assisting in the formation of collagen, the most important protein of connective tissue. Vitamin C, a water-soluble vitamin found in water-filled foods, dissolves in water and is transported in the bloodstream.

Excess amounts are excreted in the urine; however, since the body does not store vitamin C, food sources should be consumed on a regular basis. Vitamin C deficiency is manifested by decreased collagen synthesis, which can result in delayed healing and capillary fragility. Wounds may fail to heal because scar tissue doesn’t form. Ascorbic acid deficiency is also associated with impaired immune function, which can decrease the ability to fight infection.

Vitamin C supplementation has been shown to increase tensile strength and collagen synthesis by assisting in the hydroxylation of lysine and proline, major constituents of collagen.

Groups at Risk of Vitamin C Inadequacy

Smokers and passive “smokers”

Studies consistently show that smokers have lower plasma and leukocyte vitamin C levels than nonsmokers, due in part to increased oxidative stress [8]. For this reason, the IOM concluded that smokers need 35 mg more vitamin C per day than nonsmokers [8]. Exposure to secondhand smoke also decreases vitamin C levels. Although the IOM was unable to establish a specific vitamin C requirement for nonsmokers who are regularly exposed to secondhand smoke, these individuals should ensure that they meet the RDA for vitamin C [4,8].

Infants fed evaporated or boiled milk

Most infants in developed countries are fed breastmilk and/or infant formula, both of which supply adequate amounts of vitamin C [8,16]. For many reasons, feeding infants evaporated or boiled cow’s milk is not recommended. This practice can cause vitamin C deficiency because cow’s milk naturally has very little vitamin C and heat can destroy vitamin C [6,12].

Individuals with limited food variety

Although fruits and vegetables are the best sources of vitamin C, many other foods have small amounts of this nutrient. Thus, through a varied diet, most people should be able to meet the vitamin C RDA or at least obtain enough to prevent scurvy. People who have limited food variety— including some elderly, indigent individuals who prepare their own food; people who abuse alcohol or drugs; food faddists; people with mental illness; and, occasionally, children—might not obtain sufficient vitamin C [4,6-9,11].

People with malabsorption and certain chronic diseases

Some medical conditions can reduce the absorption of vitamin C and/or increase the amount needed by the body. People with severe intestinal malabsorption or cachexia and some cancer patients might be at increased risk of vitamin C inadequacy [29]. Low vitamin C concentrations can also occur in patients with end-stage renal disease on chronic hemodialysis [30].

Vitamin C and Health

Due to its function as an antioxidant and its role in immune function, vitamin C has been promoted as a means to help prevent and/or treat numerous health conditions. This section focuses on four diseases and disorders in which vitamin C might play a role: cancer (including prevention and treatment), cardiovascular disease, age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and cataracts, and the common cold.

Cancer prevention

Most case-control studies have found an inverse association between dietary vitamin C intake and cancers of the lung, breast, colon or rectum, stomach, oral cavity, larynx or pharynx, and esophagus [2,4]. Plasma concentrations of vitamin C are also lower in people with cancer than controls [2].

Cancer treatment

Oral administration of vitamin C, even of very large doses, can raise plasma vitamin C concentrations to a maximum of only 220 micromol/L, whereas IV administration can produce plasma concentrations as high as 26,000 micromol/L [49,50]. Concentrations of this magnitude are selectively cytotoxic to tumor cells in vitro [1,69]. Research in mice suggests that pharmacologic doses of IV vitamin C might show promise in treating otherwise difficult-to-treat tumors [51]. A high concentration of vitamin C may act as a pro-oxidant and generate hydrogen peroxide that has selective toxicity toward cancer cells [51-53]. Based on these findings and a few case reports of patients with advanced cancers who had remarkably long survival times following administration of high-dose IV vitamin C, some researchers support reassessment of the use of high-dose IV vitamin C as a drug to treat cancer [3,49,51,54].

Cardiovascular disease

Vitamin C has been shown to reduce monocyte adherence to the endothelium, improve endothelium-dependent nitric oxide production and vasodilation, and reduce vascular smooth-muscle-cell apoptosis, which prevents plaque instability in atherosclerosis [2,59].

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and cataracts

AMD and cataracts are two of the leading causes of vision loss in older individuals. Oxidative stress might contribute to the etiology of both conditions. Thus, researchers have hypothesized that vitamin C and other antioxidants play a role in the development and/or treatment of these diseases. High dietary intakes of vitamin C and higher plasma ascorbate concentrations have been associated with a lower risk of cataract formation in some studies [2,4].

The Common Cold

In trials involving marathon runners, skiers, and soldiers exposed to extreme physical exercise and/or cold environments, prophylactic use of vitamin C in doses ranging from 250 mg/day to 1 g/day reduced cold incidence by 50%. In the general population, use of prophylactic vitamin C modestly reduced cold duration by 8% in adults and 14% in children. When taken after the onset of cold symptoms, vitamin C did not affect cold duration or symptom severity. Overall, the evidence to date suggests that regular intakes of vitamin C at doses of at least 200 mg/day do not reduce the incidence of the common cold in the general population, but such intakes might be helpful in people exposed to extreme physical exercise or cold environments and those with marginal vitamin C status, such as the elderly and chronic smokers [83-85]. The use of vitamin C supplements might shorten the duration of the common cold and ameliorate symptom severity in the general population [82,85], possibly due to the anti-histamine effect of high-dose vitamin C [86]. However, taking vitamin C after the onset of cold symptoms does not appear to be beneficial [83].

Health Risks from Excessive Vitamin C

Vitamin C has low toxicity and is not believed to cause serious adverse effects at high intakes [8]. The most common complaints are:

- diarrhea

- nausea

- abdominal cramps

- and other gastrointestinal disturbances due to the osmotic effect of unabsorbed vitamin C in the gastrointestinal tract [4,8].

References

- Li Y, Schellhorn HE. New developments and novel therapeutic perspectives for vitamin C. J Nutr 2007;137:2171-84. [PubMed abstract]

- Carr AC, Frei B. Toward a new recommended dietary allowance for vitamin C based on antioxidant and health effects in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69:1086-107. [PubMed abstract]

- Frei B, England L, Ames BN. Ascorbate is an outstanding antioxidant in human blood plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1989;86:6377-81. [PubMed abstract]

- Jacob RA, Sotoudeh G. Vitamin C function and status in chronic disease. Nutr Clin Care 2002;5:66-74. [PubMed abstract]

- Gershoff SN. Vitamin C (ascorbic acid): new roles, new requirements? Nutr Rev 1993;51:313-26. [PubMed abstract]

- Weinstein M, Babyn P, Zlotkin S. An orange a day keeps the doctor away: scurvy in the year 2000. Pediatrics 2001;108:E55. [PubMed abstract]

- Wang AH, Still C. Old world meets modern: a case report of Nutr Clin Pract 2007;22:445-8. [PubMed abstract]

- Institute of Medicine. Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids . Washington, DC: National Academy Press,

- Stephen R, Utecht Scurvy identified in the emergency department: a case report. J Emerg Med 2001;21:235-7. [PubMed abstract]

- Padayatty SJ, Sun H, Wang Y, Riordan HD, Hewitt SM, Katz A, Wesley RA, Levine M. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics: implications for oral and intravenous use. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:533-7. [PubMed abstract]

- Francescone MA, Levitt J. Scurvy masquerading as leukocytoclastic vasculitis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis 2005;76:261-6. [PubMed abstract]

- S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. FoodData Central, 2019.

- S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: A Food Labeling Guide (14. Appendix F: Calculate the Percent Daily Value for the Appropriate Nutrients). 2013.

- S. Food and Drug Administration. Food Labeling: Revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels. 2016.

- S. Food and Drug Administration. Food Labeling: Revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels and Serving Sizes of Foods That Can Reasonably Be Consumed at One Eating Occasion; Dual- Column Labeling; Updating, Modifying, and Establishing Certain Reference Amounts Customarily Consumed; Serving Size for Breath Mints; and Technical Amendments; Proposed Extension of Compliance Dates. 2017.

- Bates CJ. Bioavailability of vitamin C. Eur J Clin Nutr 1997;51 (Suppl 1):S28-33. [PubMed abstract]

- Mangels AR, Block G, Frey CM, Patterson BH, Taylor PR, Norkus EP, et al. The bioavailability to humans of ascorbic acid from oranges, orange juice and cooked broccoli is similar to that of synthetic ascorbic acid. J Nutr 1993;123:1054-61. [PubMed abstract]

- Gregory JF 3rd. Ascorbic acid bioavailability in foods and supplements. Nutr Rev 1993;51:301-3. [PubMed abstract]

- Johnston CS, Luo B. Comparison of the absorption and excretion of three commercially available sources of vitamin C. J Am Diet Assoc 1994;94:779-81. [PubMed abstract]

- Moyad MA, Combs MA, Vrablic AS, Velasquez J, Turner B, Bernal Vitamin C metabolites, independent of smoking status, significantly enhance leukocyte, but not plasma ascorbate concentrations. Adv Ther 2008;25:995-1009. [PubMed abstract]

- Moshfegh A, Goldman J, Cleveland L. What We Eat in America, NHANES 2001-2002: Usual Nutrient Intakes from Food Compared to Dietary Reference Intakes . Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service,

- Radimer K, Bindewald B, Hughes J, Ervin B, Swanson C, Picciano Dietary supplement use by US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2000. Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:339-49. [PubMed abstract]

- Picciano MF, Dwyer JT, Radimer KL, Wilson DH, Fisher KD, Thomas PR, et al. Dietary supplement use among infants, children, and adolescents in the United States, 1999-2002. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007;161:978-85. [PubMed abstract]

- Levine M, Conry-Cantilena C, Wang Y, Welch RW, Washko PW, Dhariwal KR, et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996;93:3704-9. [PubMed abstract]

- Levine M, Rumsey SC, Daruwala R, Park JB, Wang Criteria and recommendations for vitamin C intake. JAMA 1999;281:1415-23. [PubMed abstract]

- King, CG, Waugh, The chemical nature of vitamin C. Science 1932;75:357-358.

- Svirbely J, Szent-Györgyi A. Hexuronic acid as the antiscorbutic Nature 1932;129: 576.

- Svirbely J, Szent-Györgyi A. Hexuronic acid as the antiscorbutic Nature 1932;129: 690.

- Hoffman Micronutrient requirements of cancer patients. Cancer. 1985;55 (1 Suppl):295-300. [PubMed abstract]

- Deicher R, Hörl WH. Vitamin C in chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis patients. Kidney Blood Press Res 2003;26:100-6. [PubMed abstract]

- Hecht SS. Approaches to cancer prevention based on an understanding of N-nitrosamine carcinogenesis. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1997;216:181-91. [PubMed abstract]

- Zhang S, Hunter DJ, Forman MR, Rosner BA, Speizer FE, Colditz GA, et al. Dietary carotenoids and vitamins A, C, and E and risk of breast J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:547-56. [PubMed abstract]

- Kushi LH, Fee RM, Sellers TA, Zheng W, Folsom AR. Intake of vitamins A, C, and E and postmenopausal breast The Iowa Women’s Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 1996;144:165-74. [PubMed abstract]

- Levine M, Wang Y, Padayatty SJ, Morrow J. A new recommended dietary allowance of vitamin C for healthy young women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98:9842-6. [PubMed abstract]

- Hercberg S, Galan P, Preziosi P, Bertrais S, Mennen L, Malvy D, et al. The SU.VI.MAX Study: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the health effects of antioxidant vitamins and minerals. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:2335-42. [PubMed abstract]

- Galan P, Briançon S, Favier A, Bertrais S, Preziosi P, Faure H, et al. Antioxidant status and risk of cancer in the SU.VI.MAX study: is the effect of supplementation dependent on baseline levels? Br J Nutr 2005;94:125-32. [PubMed abstract]

- Gaziano JM, Glynn RJ, Christen WG, Kurth T, Belanger C, MacFadyen J, et al. Vitamins E and C in the prevention of prostate and total cancer in men: the Physicians’ Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;301:52-62. [PubMed abstract]

- Lin J, Cook NR, Albert C, Zaharris E, Gaziano JM, Van Denburgh M, et al. Vitamins C and E and beta carotene supplementation and cancer risk: a randomized controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;101:14-23. [PubMed abstract]

- Taylor PR, Li B, Dawsey SM, Li JY, Yang CS, Guo W, et al. Prevention of esophageal cancer: the nutrition intervention trials in Linxian, China. Linxian Nutrition Intervention Trials Study Group. Cancer Res 1994;54(7 Suppl):2029s-31s. [PubMed abstract]

- Qiao YL, Dawsey SM, Kamangar F, Fan JH, Abnet CC, Sun XD, et Total and cancer mortality after supplementation with vitamins and minerals: follow-up of the Linxian General Population Nutrition Intervention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;101:507-18. [PubMed abstract]

- Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Simonetti RG, Gluud C. Antioxidant supplements for preventing gastrointestinal cancers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(3):CD004183. [PubMed abstract]

- Coulter I, Hardy M, Shekelle P, Udani J, Spar M, Oda K, et al. Effect of the supplemental use of antioxidants vitamin C, vitamin E, and coenzyme Q10 for the prevention and treatment of Evidence Report/Technology Assessment Number 75. AHRQ Publication No. 04-E003. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2003. [PubMed abstract]

- Padayatty SJ, Levine M. Vitamins C and E and the prevention of N Engl J Med 2006;355:1065. [PubMed abstract]

- Padayatty SJ, Levine M. Antioxidant supplements and cardiovascular disease in men. JAMA 2009;301:1336. [PubMed abstract]

- Cameron E, Campbell A. The orthomolecular treatment of II. Clinical trial of high-dose ascorbic acid supplements in advanced human cancer. Chem Biol Interact 1974;9:285-315. [PubMed abstract]

- Cameron E, Pauling L. Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: prolongation of survival times in terminal human Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1976;73:3685-9. [PubMed abstract]

- Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Creagan ET, Rubin J, O’Connell MJ, Ames MM. High-dose vitamin C versus placebo in the treatment of patients with advanced cancer who have had no prior chemotherapy. A randomized double-blind comparison. N Engl J Med 1985;312:137-41. [PubMed abstract]

- Bruno EJ Jr, Ziegenfuss TN, Landis J. Vitamin C: research Curr Sports Med Rep 2006;5:177-81. [PubMed abstract]

- Padayatty SJ, Riordan HD, Hewitt SM, Katz A, Hoffer LJ, Levine M. Intravenously administered vitamin C as cancer therapy: three CMAJ 2006;174:937-42. [PubMed abstract]

- Hoffer LJ, Levine M, Assouline S, Melnychuk D, Padayatty SJ, Rosadiuk K, et al. Phase I clinical trial of v. ascorbic acid in advanced malignancy. Ann Oncol 2008;19:1969-74. [PubMed abstract]

- Chen Q, Espey MG, Sun AY, Pooput C, Kirk KL, Krishna MC, et al. Pharmacologic doses of ascorbate act as a prooxidant and decrease growth of aggressive tumor xenografts in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:11105-9. [PubMed abstract]

- Chen Q, Espey MG, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB, Corpe CP, Buettner GR, et al. Pharmacologic ascorbic acid concentrations selectively kill cancer cells: action as a pro-drug to deliver hydrogen peroxide to tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:13604-9. [PubMed abstract]

- Chen Q, Espey MG, Sun AY, Lee JH, Krishna MC, Shacter E, et al. Ascorbate in pharmacologic concentrations selectively generates ascorbate radical and hydrogen peroxide in extracellular fluid in Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:8749-54. [PubMed abstract]

- Levine M, Espey MG, Chen Q. Losing and finding a way at C: new promise for pharmacologic ascorbate in cancer treatment. Free Radic Biol Med 2009;47:27-9. [PubMed abstract]

- Seifried HE, Anderson DE, Sorkin BC, Costello RB. Free radicals: the pros and cons of antioxidants. Executive summary report. J Nutr 2004;134:3143S-63S. [PubMed abstract]

- Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. Vitamin C.

- Ye Z, Song H. Antioxidant vitamins intake and the risk of coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2008;15:26-34. [PubMed abstract]

- Willcox BJ, Curb JD, Rodriguez BL. Antioxidants in cardiovascular health and disease: key lessons from epidemiologic studies. Am J Cardiol 2008;101:75D-86D. [PubMed abstract]

- Honarbakhsh S, Schachter M. Vitamins and cardiovascular Br J Nutr 2008:1-19. [PubMed abstract]

- Osganian SK, Stampfer MJ, Rimm E, Spiegelman D, Hu FB, Manson JE, et al. Vitamin C and risk of coronary heart disease in women. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:246-52. [PubMed abstract]

- Lee DH, Folsom AR, Harnack L, Halliwell B, Jacobs DR Does supplemental vitamin C increase cardiovascular disease risk in women with diabetes? Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:1194-200. [PubMed abstract]

- Myint PK, Luben RN, Welch AA, Bingham SA, Wareham NJ, Khaw Plasma vitamin C concentrations predict risk of incident stroke over 10 y in 20 649 participants of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer Norfolk prospective population study. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87:64-9. [PubMed abstract]

- Muntwyler J, Hennekens CH, Manson JE, Buring JE, Gaziano JM. Vitamin supplement use in a low-risk population of US male physicians and subsequent cardiovascular Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1472-6. [PubMed abstract]

- Knekt P, Ritz J, Pereira MA, O’Reilly EJ, Augustsson K, Fraser GE, et al. Antioxidant vitamins and coronary heart disease risk: a pooled analysis of 9 cohorts. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:1508-20. [PubMed abstract]

- Cook NR, Albert CM, Gaziano JM, Zaharris E, MacFadyen J, Danielson E, et al. A randomized factorial trial of vitamins C and E and beta carotene in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in women: results from the Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1610-8. [PubMed abstract]

- Sesso HD, Buring JE, Christen WG, Kurth T, Belanger C, MacFadyen J, et al. Vitamins E and C in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in men: the Physicians’ Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008;300:2123-33. [PubMed abstract]

- Waters DD, Alderman EL, Hsia J, Howard BV, Cobb FR, Rogers WJ, et al. Effects of hormone replacement therapy and antioxidant vitamin supplements on coronary atherosclerosis in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:2432-40. [PubMed abstract]

- Bleys J, Miller ER 3rd, Pastor-Barriuso R, Appel LJ, Guallar E. Vitamin-mineral supplementation and the progression of atherosclerosis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:880-7. [PubMed abstract]

- Shekelle P, Morton S, Hardy M. Effect of supplemental antioxidants vitamin C, vitamin E, and coenzyme Q10 for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 83 AHRQ Publication No. 03-E043. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, [PubMed abstract]

- van Leeuwen R, Boekhoorn S, Vingerling JR, Witteman JC, Klaver CC, Hofman A, et al. Dietary intake of antioxidants and risk of age- related macular degeneration. JAMA 2005;294:3101-7. [PubMed abstract]

- Evans J. Primary prevention of age related macular degeneration. BMJ 2007;335:729. [PubMed abstract]

- Chong EW, Wong TY, Kreis AJ, Simpson JA, Guymer RH. Dietary antioxidants and primary prevention of age related macular degeneration: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2007;335:755. [PubMed abstract]

- Evans JR. Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for slowing the progression of age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(2):CD000254. [PubMed abstract]

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:1417-36. [PubMed abstract]

- The Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) Research Group. Lutein + zeaxanthin and omega-3 fatty acids for age-related macular degeneration: the Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;309:2005-15. [PubMed abstract]

- Yoshida M, Takashima Y, Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Otani T, Sasaki S; JPHC Study Group. Prospective study showing that dietary vitamin C reduced the risk of age-related cataracts in a middle-aged Japanese population. Eur J Nutr 2007;46:118-24. [PubMed abstract]

- Rautiainen S, Lindblad BE, Morgenstern R, Wolk A. Vitamin C supplements and the risk of age-related cataract: a population-based prospective cohort study in women. Am J Clin 2010 Feb;91(2):487-93. [PubMed abstract]

- Sperduto RD, Hu TS, Milton RC, Zhao JL, Everett DF, Cheng QF, et al. The Linxian cataract studies. Two nutrition intervention trials. Arch Ophthalmol 1993;111:1246-53. [PubMed abstract]

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E and beta carotene for age-related cataract and vision loss: AREDS report no. 9. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:1439-52. [PubMed abstract]

- The Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) Research Group. Lutein/zeaxanthin for the treatment of age-related cataract: AREDS2 randomized trial report no. 4. JAMA Ophthalmol 2013. Online May [PubMed abstract]

- Pauling L. The significance of the evidence about ascorbic acid and the common cold. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1971;68:2678-81. [PubMed abstract]

- Douglas RM, Hemilä H. Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold. PLoS Med 2005;2:e168. [PubMed abstract]

- Douglas RM, Hemilä H, Chalker E, Treacy B. Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(3):CD000980. [PubMed abstract]

- Wintergerst ES, Maggini S, Hornig DH. Immune-enhancing role of vitamin C and zinc and effect on clinical conditions. Ann Nutr Metab 2006;50:85-94. [PubMed abstract]

- Hemilä H. The role of vitamin C in the treatment of the common Am Fam Physician 2007;76:1111, 1115. [PubMed abstract]

- Johnston CS. The antihistamine action of ascorbic acid. Subcell Biochem 1996;25:189-213. [PubMed abstract]

- Curhan GC, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ. A prospective study of the intake of vitamins C and B6, and the risk of kidney stones in men. J Urol 1996;155:1847-51. [PubMed abstract]

- Curhan GC, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Stampfer MJ. Intake of vitamins B6 and C and the risk of kidney stones in women. J Am Soc Nephrol 1999;10:840-5. [PubMed abstract]

- Taylor EN, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Dietary factors and the risk of incident kidney stones in men: new insights after 14 years of follow- up. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004;15:3225-32. [PubMed abstract]

- Lee SH, Oe T, Blair IA. Vitamin C-induced decomposition of lipid hydroperoxides to endogenous genotoxins. Science 2001;292:2083-6. [PubMed abstract]

- Podmore ID, Griffiths HR, Herbert KE, Mistry N, Mistry P, Lunec J. Vitamin C exhibits pro-oxidant properties. Nature 1998;392:559. [PubMed abstract]

- Carr A, Frei B. Does vitamin C act as a pro-oxidant under physiological conditions? FASEB J 1999 Jun;13:1007-24. [PubMed abstract]

- Lawenda BD, Kelly KM, Ladas EJ, Sagar SM, Vickers A, Blumberg JB. Should supplemental antioxidant administration be avoided during chemotherapy and radiation therapy? J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:773-83. [PubMed abstract]

- Ladas EJ, Jacobson JS, Kennedy DD, Teel K, Fleischauer A, Kelly KM. Antioxidants and cancer therapy: a systematic J Clin Oncol 2004;22:517-28. [PubMed abstract]

- Block KI, Koch AC, Mead MN, Tothy PK, Newman RA, Gyllenhaal C. Impact of antioxidant supplementation on chemotherapeutic efficacy: a systematic review of the evidence from randomized controlled Cancer Treat Rev 2007;33:407-18. [PubMed abstract]

- Heaney ML, Gardner JR, Karasavvas N, Golde DW, Scheinberg DA, Smith EA, et al. Vitamin C antagonizes the cytotoxic effects of antineoplastic drugs. Cancer Res 2008;68:8031-8. [PubMed abstract]

- Prasad KN. Rationale for using high-dose multiple dietary antioxidants as an adjunct to radiation therapy and chemotherapy. J Nutr 2004;134:3182S-3S. [PubMed abstract]

- Brown BG, Zhao XQ, Chait A, Fisher LD, Cheung MC, Morse JS, et al. Simvastatin and niacin, antioxidant vitamins, or the combination for the prevention of coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1583-92. [PubMed abstract]

- Cheung MC, Zhao XQ, Chait A, Albers JJ, Brown BG. Antioxidant supplements block the response of HDL to simvastatin-niacin therapy in patients with coronary artery disease and low HDL. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001;21:1320-6. [PubMed abstract]

Disclaimer

This fact sheet by the Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS) provides information that should not take the place of medical advice. We encourage you to talk to your healthcare providers (doctor, registered dietitian, pharmacist, etc.) about your interest in, questions about, or use of dietary supplements and what may be best for your overall health. Any mention in this publication of a specific product or service, or recommendation from an organization or professional society, does not represent an endorsement by ODS of that product, service, or expert advice.

SCHEDULE A CONSULTATION

Schedule by phone at (914) 953 2955 or fill out the online consultation request

by submitting this form you agree to be contacted via phone/text/email.

SCHEDULE A CONSULTATION

By submitting this form you agree to be contacted via phone/text/email.